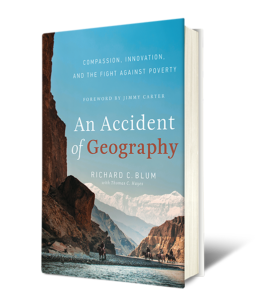

One summer in the 1950s, when I was an undergrad at the University of California at Berkeley, I took trains and hitchhiked across much of Western Europe and parts of North Africa. Barely a decade after World War II, I saw millions of people living in deplorable conditions, barely surviving. It was a shock. I never realized how difficult life was for so many. Those searing images stayed with me. In time they exerted a pull toward what is now my life’s work and loomed, distressingly and often, as I worked on An Accident of Geography.

Years later, I found myself with some fellow trekkers in the gorgeous Annapurna range of the Himalaya, led by a group of kind and knowledgeable Sherpa guides. We stayed the night in a Tibetan refugee camp in Nepal, surrounded by people who were also struggling to survive. They had few possessions, no money, no access to clean water or education, yet they were incredibly friendly and hospitable. The children of the camp came to sit in our laps, some even speaking to us in English. They laughed and smiled.

I was awestruck by their graciousness but also downcast, taken to a place even more somber than where those post–World War II memories lurked. These bright, cheerful kids were born into poverty and isolation purely by an accident of geography. They had no real opportunity in their lives other than the hard labor of subsistence farming or load bearing alongside parents and siblings on steep Himalaya mountainsides.

My buddies and I wanted to help. We started modestly, marshaling funds to educate children of our Sherpa guides’ communities. We were inspired further by remarkable commitments initiated by Sir Edmund Hillary, my boyhood hero who eventually became a dear friend. His Himalayan Trust has developed schools, clinics, and clean-water projects in villages in the shadows of Mt. Everest since 1960.

“For the Sherpas who live [near Mt. Everest], life has few privileges,” he said. “I was brought up to believe that if you had a chance to help people worse off than you, you should do it.”

Walk the villages, Sir Ed advised. Listen to people. They will tell you what they need.

And we did.

The foundation we started 35 years ago has been a continuing passion. Our American Himalayan Foundation now touches the lives of 300,000 Sherpas, Nepalis, and Tibetans every year through schools, medical clinics and hospitals, cultural restoration, protection from sex trafficking, and more. We continue to partner with Sir Ed’s organization eight years after his passing.

The foundation we started 35 years ago has been a continuing passion. Our American Himalayan Foundation now touches the lives of 300,000 Sherpas, Nepalis, and Tibetans every year through schools, medical clinics and hospitals, cultural restoration, protection from sex trafficking, and more. We continue to partner with Sir Ed’s organization eight years after his passing.

When you carry a deep passion, what might seem like magical thinking can lead you to something very real.

In this blog, I’ll share some stories and lessons from the pages of An Accident of Geography. We have raised our sights beyond the Himalaya in recent years, to championing global development. These experiences have given my life purpose and meaning. I believe helping others less fortunate can do the same for yours. Everyone has something they can contribute.

Leave a Reply