I thought I had seen the worst of the world’s extreme poverty in Tibet and Nepal, but people I met in Ethiopian villages and across the western border in South Sudan on my first visit in the late 1990s were emaciated, lacking food and the most basic health care.

Trachoma may have been Ethiopia’s most feared plague at the time.

Its people had the highest rates of trachoma infection in the world—two hundred times above what the World Health Organization has said is the threshold for concern. Yet trachoma was accepted in the villages as a way of life, a curse, and remains so in many parts of the country. An estimated minimum of 67 million Ethiopians remain at risk today.

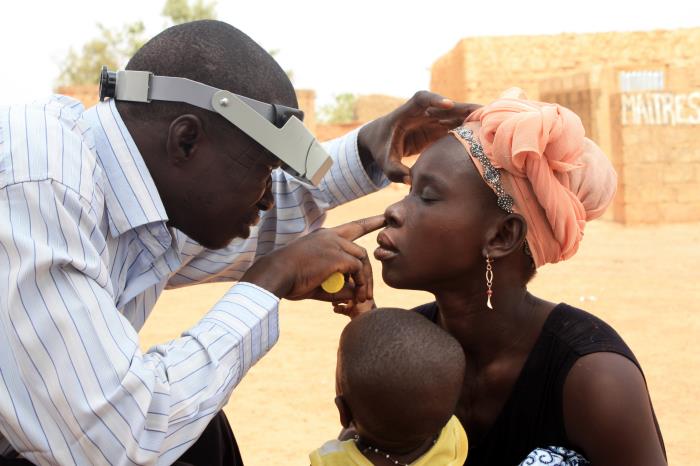

A bacterial infection spread by flies that breed on human feces or by simple contact between one person and another, trachoma is the leading cause of preventable blindness worldwide.

Once an upper eyelid is infected, the eyelid turns inward, causing the lashes to scratch the cornea—painfully, with every blink of the eye—and leading to scarring, diminished vision, and eventually (after repeated infections) blindness. The infection almost always occurs in both eyes. (In above photo, a health worker in Ghana examines a woman’s eyes for any signs of trachoma.)

Effective prevention involves nothing more than rudimentary infrastructure and basic hygiene. Building pit latrines with covers and small anterooms is necessary to curb the fly population. Teaching villagers and schoolchildren to wash their hands and faces helps prevent infections. Surgery and antibiotics are simple ways to correct damaged eyelids and restore a patient’s vision.

As we emphasized in last week’s post, The Carter Center has played a massive role in sharply reducing outbreaks of preventable diseases in poor, rural areas with little formal health care. The center and its partners have prevented the suffering of millions of people. President Carter and his teams travel to Africa and other stricken areas all the time, talking with everyone from heads of state to local leaders to the very people afflicted with preventable tropical diseases. (In photo below from 2007, a health team member, once a driver for Carter Center staff in Ghana, demonstrates for Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter how clean water is accessible for hand washing.)

A Carter Center trustee for many years, I have walked the village dirt roads with Jimmy in Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan, and other desperately poor countries where The Carter Center has been a respected force in curtailing these plagues.

By teaching basic hygiene, building latrine pits, administering antibiotics, and performing simple surgeries on infected upper eyelids, agents of the center and its many allies have demonstrated – as with Guinea worm – how a disease tormenting humankind with needless suffering and pain for thousands of years can now be prevented. Evidence of trachoma can be traced to as early as 8,000 B.C.

President Carter already was marshaling funds and teams to tackle Guinea worm, river blindness, and other preventable diseases near the horn of Africa when he added trachoma to The Carter Center agenda. He knew trachoma could be corralled and stopped because as a boy he had seen his mother, Lillian Carter, a nurse, treat trachoma victims in southern Georgia.

The front lines of the center’s battle to eradicate trachoma stretched from the center of Ethiopia southwest to the Sudanese border, where the center and other health organizations were just starting programs to fight the disease.

The scenes were shocking to me. I was standing at ground zero of the world’s worst trachoma outbreaks. The corneas of people with advancing trachoma were cloudy white, ghostly. Trachoma presents the greatest risk to communities through their children, who often spread the disease to mothers or other family members who are trying to care for or comfort them. Partially because of that maternal instinct, experts say, women are twice as likely as men to contract the disease.

Estimates among global health professionals suggest cases are so numerous that advanced trachoma blinds one person every fifteen minutes. More than half of the children I saw nearly twenty years ago were infected.

In 2015, The Carter Center estimated that 800,000 eyelid surgeries were required to prevent total blindness in trachoma victims who had suffered multiple scarring infections on their corneas. To accomplish this goal, health workers need to be trained and health centers built. The 15-minute surgeries alone are comparatively simple. Providing the resources required is more complex.

In 2013 alone, The Carter Center supported fifty-eight thousand corrective eye surgeries—a quarter of the surgeries performed worldwide—conducted by local health workers who were trained and equipped for the procedures.

In the same year, the center supported construction of more than 150,000 household latrines, upping the total since 2002 to approximately 3.1 million.

Last year, the center joined with one of its allies, the Noor Dubai Foundation of the United Arab Emirates, in a four-year project aiming to sharply reduce the incidence of trachoma in Ethiopia’s hardest hit region by reaching as many as 16 million people with basic prevention, surgeries and other focused health services. Last month, the OPEC Fund for International Development said it would contribute $800,000 to the center’s trachoma prevention projects in Mali and Niger.

The World Health Organization’s goal is to totally defeat trachoma globally in three years. The Carter Center’s work is an inspiring part of that campaign.

** **

To learn more about Carter Center trachoma treatment and prevention programs, please visit: https://www.cartercenter.org/health/trachoma/index.html

Photos courtesy of The Carter Center

Leave a Reply