You can’t fathom how deeply endemic superstition and ignorance are to poor, isolated communities until you walk the villages and hear the stories. The worst of them can leave you stunned, heart-broken, and angry.

Our foundation’s field director in Nepal, Bruce Moore, once met a man in a remote village three hours north of Kathmandu who expressed delight at having seven daughters. Surprised given the setting, but brightening, Bruce asked: why? “You know, girls are worth money,” was the reply.

This man had sold his sister into slavery for $50, and, with no hint of remorse, anticipated auctioning his daughters into brothels or bonded labor, each perhaps for as much as $500 – a year’s average income in Nepal. “I had been looking into the eyes of a devil,” Bruce recalls. He was shaken, one of the worst days of his life.

When Tara was seven years old and hobbled by a hip infection, her parents called in a local shaman for a cure. He offered a prayer for her recovery, cracking an egg for effect. The egg was payment along with three roosters for the shaman’s services. Tara continued to suffer, though, limping with pain into a now uncertain future.

At age four Buddhi was like most other little boys in the remote mountains of Nepal: poor, but too young to worry about anything beyond running around and playing with friends. One day he tripped and fell into a cooking fire in his family’s one-room home. Without basic care to bind the wound, Buddhi was disabled, a cripple. The healing flesh on his lower right thigh and upper calf fused. He couldn’t walk.

Five years later, Buddhi’s parents abandoned him.

“Children in the hinterlands of Nepal have no access to the kind of doctors we would bring our children to in a nanosecond,” says Mike Klein, a lawyer, humanitarian, and longtime director of our foundation. “Many are often treated as outcasts, as if some evil spirits must have made them that way. It’s tragic.”

These stories are heart-breaking. But for many like Mike who make the time to hear them in the field, and respond, they can be highly motivating. People who commit to helping the poor improve their lives find the experience tremendously rewarding.

Our program to protect Nepali girls from human traffickers is an example. Hundreds of donors gather each spring to hear the latest news – and receive heart-touching inspiration – at the STOP Girl Trafficking (SGT) fund-raising dinner in San Francisco. (This year’s event is March 23.)

More than 20,000 Nepali girls from the poorest families have found peace in SGT schools over the past two decades, protected from traffickers and getting an education. Many live in mountains north of Kathmandu, along steep, dirt roads where Bruce Moore and his team less often encounter ignorance that treats girls and women like cattle. Often they find the opposite: communities that now value and respect their educated daughters.

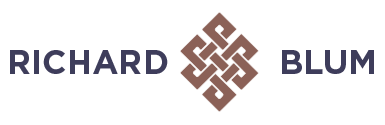

A rented, three-story apartment building (left) was the first home of the Hospital and Rehabilitation Center for Disabled Children, in the 1980s. A new world-class facility (right, foreground), now with 74 beds and 130 onsite staff, opened outside Kathmandu in 1997.

For Tara, a magical moment for her future happened when an American volunteer for Save The Children spotted her standing awkwardly on a street corner, favoring her bad hip. The volunteer had the presence of mind to relay a photo of Tara, now 16, via mobile phone to HRDC’s staff. Tara was admitted the next day.

A simple surgery reopened and aligned the joint that had been fused by the untreated infection. Tara was able to stand straight…the first time in nine years. Now in her 40s, married with one son, you can find her making her rounds at HRDC with only a slight limp. She’s a housemother, comforting and caring for the children. “Mommy,” is how they greet her.

Buddhi was found months after he was abandoned by his family, hobbling on one leg, propped by his only possession, a thin, battered branch he used as a crutch. An empathetic woman in the village encouraged him to seek out a children’s refuge in Kathmandu, where Bruce soon discovered Buddhi’s alarming condition and brought him to the gleaming new orthopedic hospital that had opened only a few years before.

Buddhi’s gateway to a better life, a story repeated often at HRDC, was a simple surgery: releasing the connective scar tissue, then carefully straightening his crippled leg. In the first of three photos at the top, Buddhi is in obvious discomfort, one day after surgery. In the second, one week later, he’s beaming. In the third, a year later, he’s a normal eleven-year-old boy again… jousting (on the left) with his friend Krishna.

Later, in high school, Buddhi dreamed of a future in health services. He wanted to pay forward, to help disabled children. To have any chance, though, Buddhi had to walk: 45 minutes a day, each way, to attend college classes. He couldn’t afford the bus.

A remarkable 90 percent of former HRDC patients have shared with Buddhi the same goal: to help disabled children through health services. When you realize that HRDC has completed 38,000 surgeries in the past three decades, this almost universally shared vision of former patients may already be generating profound benefits for Nepal.

Now 26 years old, Buddhi is in his final year of a master’s degree program in microbiology. We believe he’s going to deliver on his pledge to help. Don’t you?

Washington-based lawyer and humanitarian Mike Klein, right, with HRDC founder Dr. Ashok Banskota. “You can’t help being with these crippled children – about to be restored to more complete lives – without being emotionally involved,” Mike says. “The joke is, I go there, I cry, and I write a check.”

To learn more about the STOP Girl Trafficking dinner on March 23, please visit the American Himalayan Foundation Events page.

To learn more about healing children in Nepal, please visit the American Himalayan Foundation Healthcare blog and the Hospital and Rehabilitation Centre for Disabled Children.

Photos courtesy of the American Himalayan Foundation.

Leave a Reply