An absorbing New Yorker piece last month portrayed how solar-power gadgets and their entrepreneurs are bringing electricity for the first time to hundreds of thousands of poor Africans.

Many of these increasingly affordable gadgets and their durable quality are the handiwork of American-led companies. This raises an intriguing question: Can solar power bolster America’s uncertain prospects as a future trading partner in Africa?

“Electrifying Africa is one of the largest development challenges on earth,” writes author Bill McKibben, an environmental activist who teaches at Middlebury College. But, he adds, costs and pricing of solar electricity are falling rapidly.

These anticipated market forces were part of the inspiration behind Power Africa, President Obama’s most ambitious program to accelerate U.S.-Africa trade, established late in his second term.

Power Africa’s goal is bringing electricity to sixty millions homes and businesses in sub-Saharan Africa. Making possible for the first time basic conveniences such as lighting, electric fans, mobile-phone chargers and even televisions. More than 400 projects have been approved since 2013. The U.S. Agency for International Development, World Bank and African Development Bank all participate on teams with major companies, entrepreneurs and non-profit leaders that help local officials, experts and customers in parts of Africa set priorities and take action.

** **

What are the Trump administration’s policies on African trade and investment? It is not yet clear.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross asserted last month that Africa is a “place of opportunity.” He indicated that the Trump administration will continue the Obama-era presidential advisory committee on doing business in Africa, and, as each U.S. president has since Bill Clinton, make expanding trade a priority over foreign aid. So far, so good.

But, as Brookings advisor Witney Schneidman observed, Ross was silent on negotiating more bilateral investment treaties, and policies to promote higher levels of private U.S. investment and exports in Africa. These actions are needed. According to the African Development Bank, exports from the U.S. to Africa declined sharply to $22 billion in 2016, from $38 billion in 2014. The decline of African exports to the U.S. was even more pronounced, to $26.5 billion in 2015 from $113 billion in 2008.

As the economies of Asia and Africa combined overtake Western economies in average annual growth in output and income, Africa’s 54 nations collectively hold big potential — including potential for high rates of return on investment.

Most African nations have young, fast-growing populations. Far faster than desired. No other region of the world will come close to adding more people during the next three decades. According to the United Nations Population Division, Africa’s population has doubled to 2.4 billion since 1980, and will increase by another 1.2 billion by 2050. Meanwhile, fifty-one developed nations collectively will lose population by then.

African countries are going to need massive capital inflows to build infrastructure. Investors could reap attractive yields. If the stars align, an alluring virtuous circle could take hold. Infrastructure spending can create millions of middle-class jobs and raise living standards. More opportunities for jobs and education can fight high unemployment, mass migration, and political unrest and reduce extreme poverty.

Yet official corruption, inefficient banking and financing systems, unreliable governance and rule of law, peace and security concerns and lack of savings continue to confound investors within and outside many African nations that need their capital.

The Group of 20 nations flagged those issues in a report from Hamburg last month. Yet they were optimistic, locking arms with several African leaders to encourage more investment, more capital inflows. Germany, arguably now the world’s leading voice for free trade, took the lead on this new campaign.

Days before the Group of 20 meetings, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government put finishing touches on what’s being called Germany’s version of a Marshall Plan for Africa: a comprehensive economic package with touches echoing U.S. support of Western Europe’s recovery from ruins after World War II. Leaders of nine African nations pledged in Hamburg to tighten standards in banking and finance and improve accounting transparency. This happened the day before their finance ministers pitched investors on projects designed for appealing returns.

** **

High-return investments have been a vanishing species in global finance since the Great Recession. As we noted last month, more than $8 trillion in investable funds worldwide is sitting in negative-yield bonds issued in industrialized economies. Investment managers are under pressure, searching for higher returns.

Does the smart money in Germany believe Africa can be part of the solution? Yes. Despite recent trends, more U.S. investors appear to agree, putting solar power higher on their agenda. Financiers based mainly in Silicon Valley or Europe, including billionaires such as Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, are the sources of capital fueling solar’s African expansion.

The New Yorker’s McKibben says more than $200 million in venture capital was pledged last year, up from $19 million four years ago. Financiers are backing “many Western entrepreneurs (who) see solar power in Africa as a chance to reach a large market and make a substantial profit.”

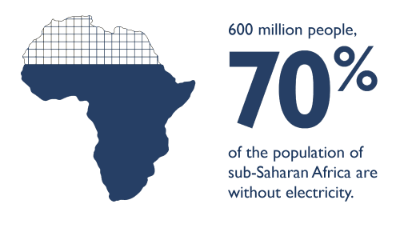

There are big risks, of course. Unproven business models. Prospective customers with no credit records. Unpredictable government policies and currency swings. Yet the market opportunity, as McKibben rightly says, is enormous. Two of every three people today in sub-Saharan Africa … 600 million people … have no access to electricity. That ratio is going to be reversed. Much sooner than most of us can imagine.

In Tanzania, not far from Mount Kilimanjaro, the thirty-eight-year-old co-founder of a U.S. start-up that has raised $55 million is a believer. “This is what an emerging economy looks like,” Xavier Helgesen, CEO of Off-Grid Electric, told McKibben. “This is young people, this is entrepreneurialism, this is where growth will be.”

** **

To read more about how Africa can attract investment, see this July 19 Brookings article: Six Steps to Start Changing How Africa Does Development

For an update on China’s leading role in aid and investment for Africa, see in the July 22 issue of The Economist: China Goes to Africa

To read more about U.S. policy and Africa, see this July 18 U.S. News article: “America First” May Put Africa Last

Photo and graphic courtesy of United States Agency for International Development.

Leave a Reply